Nurse Suicide Prevention/Resilience

DISCLAIMER: The content provided on this webpage is general in nature and does not constitute legal or medical advice. This webpage is for reference only. Always consult with a qualified health care provider for any questions you may have regarding thoughts of suicide. If you believe someone is at imminent risk of harming themselves and is refusing help or you have reason to believe someone has harmed themselves, call 911. Laws vary by jurisdiction, locality, state, or country; please follow the laws of your specific jurisdiction and consult with an attorney if you have any questions regarding the laws of your jurisdiction.

ADDITIONAL DISCLAIMER: Programs, resources, or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage are for illustrative purposes only. ANA does not endorse any program, resource or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage.

Introduction

Nurses are at higher risk of suicide than the general population. Ironically, one of the key risks is related to being a nurse. Nurses have more known issues about the job or work prior to death by suicide than others.1

The profession of nursing is fertile soil for risk factors of suicide.2

- Exposure to repeated trauma

- Scheduling long, consecutive shifts

- Repeated requests for overtime

- Workplace violence, incivility, and bullying

- Inadequate self-care

- Isolation from family and friends

- Fearing for one’s safety or the safety of loved ones

- Financial stressors

- Access to and knowledge of lethal substances

- Constant, high workplace stress

- Loneliness after relocation, transfer, or new job

- Issues with management

- Work/life role conflict

- Feeling unsupported in the role

- Feeling like you don’t belong

- Feeling unprepared for the role

- Fear of harming a patient

- Being evaluated for substance use disorder

- Depression

Unfortunately, a mindset still exists that stigmatizes asking for help. We need to change our perspective to normalize conversations about mental health and wellness. Creating an atmosphere of acceptance and empathy can send the message: “It’s okay to not be okay”. Suicide is preventable. To stop nurses from dying by suicide, we must accept that suicide happens and implement best practices to mitigate the risk.3 Educating ourselves on how to recognize the signs of a colleague at risk is important. Nurses have been at higher risk of suicide than the general public for many years.1 Now with the added stressors of social unrest and the Coronavirus pandemic, we are at even greater risk.4 There are no known foolproof ways to prevent all suicides. However, we can learn ways to reach nurses in the dark place of depression to reduce the risk of a nurse acting on their suicidal thoughts.

Resources:

- Nurse Suicide: Breaking the Silence - The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) discussion paper including work and individual prevention strategies as well as current statistics

- American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA’s) Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurse Essential Competencies for Assessment and Management of Individuals At Risk for Suicide

- American Association of Suicidology’s (AAS) website toolkits and other vast resources

- Johnson and Johnson’s See You Now Podcast: Nurses on Life Support: 10 min. podcast about nurse suicide.

- NIMH » Assessing Suicide Risk Among Childbearing Women in the U.S. Before and After Giving Birth (nih.gov)

Research Articles:

- Davidson, J. E., Proudfoot, J., Lee, K. E., Terterian, G., & Zisook, S. (2020). A Longitudinal Analysis of Nurse Suicide in the United States (2005-2016). Worldviews on evidence-based nursing / Sigma Theta Tau International, Honor Society of Nursing.

- Davidson, J. E., Accardi, R., Sanchez, C., Zisook, S., & Hoffman, L. A. (2020). Sustainability and outcomes of a suicide prevention program for nurses. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing / Sigma Theta Tau International, Honor Society of Nursing.

- Davidson, J.E., Proudfoot, J., Lee, K. & Zisook, S. (2019). Nurse suicide in the United States: Analysis of the Center for Disease Control 2014 National Violent Death Reporting System dataset. Psychiatric Nursing, 33(5), 16-21.

- Choflet, A., Davidson, J., Lee, K.C., Ye, G., Barnes, A., & Zisook, S. (2021). A comparative analysis of the substance use and mental health characteristics of nurses who complete suicide. Journal of Clinical Nursing. Published online, see https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15749.

- Davidson, J.E., Ye, G., Parra, M.C., Barnes, A.. Harkavy-Friedman, J. & Zisook, S. (2021). Job-related problems prior to nurse suicide, 2001-2017: A mixed methods analysis using natural language processing and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 12(1), 28-39.

Getting the Help YOU Need NOW

Table of Contents:

- Helping someone else

- Safety Planning

- Firearm & Medication Safety

- Risky Substance Use and Substance Use Disorder

- Supporting a colleague with risky behavior outside of work

- When a colleague presents at work impaired

- Suicide Prevention in the Educational Setting

- What you can do for yourself now

DISCLAIMER: The content provided on this webpage is general in nature and does not constitute legal or medical advice. This webpage is for reference only. Always consult with a qualified health care provider for any questions you may have regarding thoughts of suicide. If you believe someone is at imminent risk of harming themselves and is refusing help or you have reason to believe someone has harmed themselves, call 911. Laws vary by jurisdiction, locality, state, or country; please follow the laws of your specific jurisdiction and consult with an attorney if you have any questions regarding the laws of your jurisdiction.

ADDITIONAL DISCLAIMER: Programs, resources, or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage are for illustrative purposes only. ANA does not endorse any program, resource or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage.

Important: If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org. These connect to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

When you are in crisis there is help available. You are not alone. Call, text, or chat.

Depression is a treatable condition. We are not immune to the effects of depression. Calling for help can save your life.

Additional options:

- Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org. These connect to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

- Call 911 immediately.

- Contact your health care provider now.

Clinician friendly hotlines

- Safe Call Now - crisis referral service for public safety employees, emergency services personnel and their families. 206-459-3020.

- Disaster Distress Helpline – Call 1-800-985-5990 or text TalkWithUs to 66746. Run by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA). A 24/7, 365-day-a-year, national hotline providing crisis counseling for those in emotional distress related to natural or human-caused disasters.

- Crisis Text Line – 24/7 crisis support for frontline health workers from trained crisis responders. USA – Text “HOME” to 741741

Helping someone else:

People who are feeling depressed or suicidal are often in too much crisis to call for help on their own. It takes a friend or colleague to encourage them to do so, or to actually help them make the call. Depression is a treatable condition. We are not immune to the effects of depression. Calling for help can save the lives of colleagues.

Nurses are socialized to ‘play through the pain’ or ‘buck up and take it’. This makes it difficult to recognize when a nurse is having overwhelming feelings of sadness, depression, or is reaching the point where they can no longer compensate to continue to function. Using the acronym AIR (Awareness/Identify/Recognize) will assist you in identifying someone at risk of suicide.

AWARENESS

Have awareness of the warning signs often seen in someone in crisis who may be at risk for suicide. These are some of the many warning signs:

- Talking, writing or creating art about wanting to die or to kill themselves

- Looking for a way to kill themselves; searching online for a method/plan

- Talking about feeling hopeless or having no reason to live

- Talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain

- Talking about being a burden to others

- Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs

- Acting anxious or agitated

- Sleeping too little or too much

- Rumination: Cannot get bad thoughts out of their head

- Withdrawing or isolating themselves

- Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge

- Giving away belongings

- Extreme mood swings

- Reckless behavior

- Self-injurious behavior such as cutting

- It feels like this person needs more help than a friend can provide

Note that someone can be suicidal and not overtly demonstrate any signs or symptoms of suicidal intention. Self-injury is sometimes, but not always a precursor to suicidal behavior and warrants mental health evaluation.

Resources:

- SPRC’s The Role of Co-Workers in Preventing Suicide in the Workplace

- Centre for Suicide Prevention’s toolkit Self-harm and Suicide This resource is from Canada and contains information on self-harm and attempted suicide.*

*This resource originates outside of the United States. Some resources or information may not be applicable or available in the United States.

IDENTIFY

(A) Identify the person at risk

Have the Conversation

The most important thing to do is start a conversation with the person. Empathy makes a powerful connection to reduce loneliness and risk. Direct questions can be life-saving. However, do not put your own self at risk.

- Do’s: Have the moral courage to say “Are you thinking of suicide?” “Are you feeling so bad that you are thinking of killing yourself?”

- Don’ts: Don’t attempt to minimize their feelings by saying things like: “It is not that bad” “I know exactly how you feel” “At least....” For a short video on empathy, visit this one from Brene Brown.

Key components to having the conversation:

- Scan the environment and practice situational awareness before initiation.

- If you feel you are at risk, call EMS first.

- Ask if they feel suicidal, if yes, ask if they have a plan.

- If they have a plan, stay with them until they get help.

- Provide authentic presence.

- Provide empathy.

- Be curious: “Tell me more.”

- Show that you care.

- When person in crisis reaches out, show up if it is safe to do so.

- Name the emotions.

- Paraphrase back what you have heard.

- Ask if it is OK to work with them to get help.

- While honoring the person’s rights, acknowledge that their intent makes you worried.

- Know your resources and connect.

- Don’t fall into the expert trap, be a colleague, not a teacher.

- No judgement: Do not try to make them feel anything other than what they feel.

- Do not leave the person alone if they admit to thoughts of harm. Get help right away.

- Create an opportunity for the person to be willing to follow up with you again. Before leaving, discuss when to checkback. Make a follow up safety plan.

If youare familiar with motivational interviewing, these skills can be used to help with this discussion. Motivational interviewing is a collaborative conversational style for strengthening a person’s own motivation for commitment and change using empathy and a collaborative approach. Empathy is key. With motivational interviewing there is no judgement. The discussion becomes a partnership and focuses on next steps.

Reference:

- Hoy, J., Natarajan, A., & Petra, M. (2016). Motivational interviewing and the transtheoretical model of change: Under-explored resources for suicide intervention. Community Mental Health Journal, 52, 559-567.

(B) Identify coworkers who might be at risk for suicide by learning evidence-based methods.

To identify a colleague who might be at risk for suicide and support them to obtain treatment, individuals or organizations can offer training on peer suicide evaluation and self-screening tools, such as the videos prepared by Dr. Sharon Tucker at The Ohio State University. This series of 8 videos are available to the public and go through examples of words to say to someone you think is at risk of suicide.

AFSP’s “Have the Convo”: This is phrased in lay language for anyone to learn how to talk to someone you think is at risk.

Although centered around physicians and residents, this video from the AFSP introduces how to bring up the conversation and why.

(C) Identify through Proactive Screening

A proactive approach to regular screening helps to identify those with mental health condition or risky substance use before it becomes a matter of suicidal ideation or legal action.

The Healer Education, Assessment and Referral (HEAR) program5 based upon AFSP’s Interactive Screening Program6 is a comprehensive screening that can be deployed by any organization to proactively evaluate risk of faculty/employees/students. This anonymous encrypted program requires that the organization have therapists at hand to engage through encryption and a referral system for those identified at risk. This process is cost-effective, can be scaled to any size or type of organization, and has been operational for over 10 years successfully transferring depressed and suicidal clinicians into treatment.

Resources:

KPBS special podcast Study: Nurses at Greater Risk of Suicide than Others explains the HEAR program.

RECOGNIZE

Recognize the urgency to intervene

Don’t hesitate. Assume that you are the only one that has noticed the colleague in distress. Take the initiative to speak up. Do not wait until you are ‘sure’. Trust your gut. If something is making you feel that a colleague is in trouble, you could be wrong, but by speaking up at least they know that you care.

Resources:

- AFSP’s Training Programs on Mental Health First Aid and more.

- *Suicidal Thoughts & Behaviours Guidelines from Mental Health First Aid Australia*

- US Dept. of Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD offers free Psychological First Aid online training.

- Zero Suicide in Health and Behavioral Health Care – contains multiple resources including toolkits, training, and podcasts

*This resource originates outside of the United States. Some resources or information may not be applicable or available in the United States.

Pursuant to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), information regarding an individual’s health or medical information is protected health information, including an individual’s mental health condition. See, 42 U.S.C. § 1320d(4). Therefore, protected health information of an individual should not be shared without that individual’s consent. In the case of a suicide, information regarding the individual’s cause of death should not be shared without the consent of the person(s) with authority to provide consent. 45 C.F.R. §§ 164.508, 164.510.

Safety Planning/Removing Access to Lethal Means

Create Your Own Personal Safety Plan

Self-care is key. Talking about the issue with trusted colleagues and/or a trusted family member or friend is a great start to dealing with the stress caused by this issue. Developing a plan of self-care and encouraging the same for others can mitigate stress and provide a way to deal with oppressive feelings that can beset anyone at any time.

Thinking about suicide can happen to anyone unexpectantly. Develop a personal safety plan in advance. Be familiar with your resources to make it more likely that you will use available resources when a crisis occurs in your life. A Safety Plan helps you to think about warning signs, coping strategies, people who help to calm you or distract you from problems, people to call for help, and emergency phone numbers.

Resources:

Firearm & Medication Safety (photo)

The use of firearms amongst nurses who complete suicide is rising. Amongst male nurses, firearms are the most common method of suicide. Screening for risk of suicide needs to include the question of whether or not the person at risk has access to a firearm. If the answer is yes, it is important to have the firearm removed from the home until after successful treatment. Removing the firearm from the home is an evidence-based approach to reducing incidence of suicide. Suicide is often impulsive. Removing the chosen method makes it more likely the depressed person can work through the impulse to get help instead of completing the suicidal act. The same is true with medications. If the person has a plan of completing suicide by medications found in the home, remove the medications. When medications or firearms cannot be removed from the home, safety measures can be taken by storing them in a safe or fingerprint-activated (biometric) safe. View the Suicide Prevention Resource Center’s CALM: Counseling on Access to Lethal Means webpages. Counseling on access to lethal means is an evidence-based approach to suicide prevention. 7

Nurses who are gun owners are encouraged to follow firearm safety recommendations: Store firearms locked and unloaded. Store ammunition separately from firearms. Using firearm safety precautions may also save the life of a friend or family member.

Resources:

- American Foundation of Suicide Prevention’s (AFSP) Firearms and Suicide Prevention.

- NSSF The Firearm Industry Trade Association’s Suicide Prevention Toolkit Items.

- AFSP’s brochure Firearms and Suicide Prevention for gun owners about suicide and gun safety and items that can be purchased for safe storage.

- HHS How to Safely Dispose of Drugs

Risky Substance Use and Substance Use Disorder

Many nurses use substances such as alcohol and other drugs in a way that places their health at risk. These behaviors are best understood on a continuum, where one end represents no or low use of substances and little risk of harm and the other end represents acute addiction and extreme risk for harm. In the middle of the continuum, some find themselves using alcohol or drugs in a way that negatively impacts their health and wellbeing, and also places them at risk for developing an addiction.

For that reason, this section addresses not only substance use disorder (defined by SAMHSA as recurring use of alcohol and/or drugs resulting in significant impairment, including health issues, disability, and unable to meet work, school, and/or home responsibilities) but also risky substance use (defined as any substance use above recommended limits) which can negatively impact health and wellbeing. Both risky substance use and substance use disorder can be detected by routine proactive anonymous encrypted risk screening. In this manner, the person at risk may receive help before found at work impaired, diverting medications, or driving under the influence. Also see this.

General Resources:

- Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health

- NIH’s Rethinking Drinking website: Information on what constitutes a drink, warning signs and resources to make a change.

Research Articles:

- Russell, K. (2020). Components of nurse substance use disorder monitoring programs. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 11(2), 20-27.

- Smiley, R. & Reneau, K. (2020). Outcomes of substance use disorder monitoring programs for nurses. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 11(2), 28-35.

There are two different scenarios in which nurses can help colleagues with substance use disorder or risky substance behavior: a) Outside of work and b) when presenting at work impaired.

Supporting a colleague with risky behavior outside of work

If you suspect that a colleague is having issues with risky substance use outside of work, and can talk with them until they independently come to the realization that they need to change behaviors or obtain treatment, it can spare the nurse disciplinary action in the future while possibly preserving their position. A nurse who realizes that they need help can take a leave of absence to obtain treatment without disclosing the cause of the leave to their supervisor. Remembering that there is a continuum of substance use behaviors, having the difficult conversation with a colleague who is heading in the direction of substance use disorder can help them find a way back.

Please check to see your state’s position on mandatory reporting as well as any requirements by your organization.

Many organizations have instituted Peer Support programs 8,9 that provide special training to volunteer Peer Supporters. The trained colleagues use skills of empathic communication and motivational interviewing to support colleagues emotionally through difficult situations and refer to treatment as indicated. These skills can be applied to when talking to a colleague openly about substance use issues with the intention of the at-risk nurse identifying within themself that it is time to take action for change.

Having the courage to talk to a colleague who is struggling with risky behavior prior to the point where the behavior escalates to being found impaired on the job can save a life. Nurses die by suicide during investigations for substance use disorder. Nurses are psychologically harmed by the thought of losing their license or connection to the profession.

Resources:

- NCSBN’s State by State “Alternative to Discipline/Health Practitioner Monitoring Programs”

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing’s (NCSBN) Substance Use Disorder Information

- American Association of Nurse Anesthetists’ Substance Use Disorder Workplace Resources

When a colleague presents at work impaired

Each state has their own process for managing nurses found at work impaired with substance use disorder. For patient safety the situation is reported to a manager who will remove the nurse from duty and then follow the organizational process. Substance use disorder is a disease that is treatable. Ethically, we have a duty to support the nurse through treatment and welcome them back to the workforce.

Resources

- The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) has evidence-based resources that any organization can use to frame a positive non-punitive approach to supporting nurses with substance use disorder.

- American Association of Nurse Anesthetists’ Substance Use Disorder Workplace Resources

- NCSBN’s State by State “Alternative to Discipline/Health Practitioner Monitoring Programs”

- American Psychiatric Nurses Association’s Substance Use Resources

- From the Journal of Addictions Nursing article: Programs and Resources to Assist Nurses With Substance Use Disorders (2016).

- Georgia Nurses Association Peer Assistance Program is an example of a peer assistance program.

- AANA’s Substance Use Disorder - Peer Support: An Empathetic Information Resource Podcast that discusses SUD in healthcare practitioners. How do we, from a caring and helpful perspective, address this issue within ourselves or others? Approximately 18 minutes in length.

- Understanding Substance Use Disorder in Nursing Free course from NCSBN-discusses substance use, abuse, and addiction, early identification and intervention, protecting the public, and treatment, recommendation and return to practice.

Suicide Prevention in the Educational Setting: Student, Staff, and Faculty

Suicide among students, faculty, and staff in an educational setting is not a new issue. However, while any preventable death is tragic, those moments can be a clarion call to address this issue. The good news is that help is available from a variety of resources. If you have not reviewed the other information regarding suicide, available from the ANA beyond this section, please look over them after viewing these resources.

Research:

- A two-minute presentation providing a brief overview of studies on suicide in nursing students can be found here.

- A PDF version of the PowerPoint presentation used in this video with links to the various studies and reference citations can be found on the first five slides by clicking here.

What Can Colleges and Universities Do NOW?

A variety of programs have been designed with the aim of sharing the attitudes, knowledge and skills needed to help deal with and try to reduce the risk of suicide in the educational setting. These programs include:

- SAVE: Suicidal Behaviors ~ Assessment Interview ~ Value Student ~ Evaluate – Referral

- Developing a protocol dealing with a student suicide

- Kognito: avatar-based suicide risk prevention training

- CPR Camp: a three day retreat to assist student nurses in dealing with nursing school stress

- hCATS to BARN holistic training program that provides students suicide mitigation training, including Question, Persuade, and Refer (QPR) methods, as well as how to deal with nursing school stress (see below resource presentation for more information).

- The Jed Foundation offers programs, resources and more for teen and young adult emotional health and suicide prevention.

- Active Minds, a nonprofit organization for young adult mental health resources, has many programs for campuses and more!

Resources:

- An overview of the above programs, along with other programs that are available but not reviewed, with citations and contact information can be found by clicking on this link and going to the two-minute mark in this presentation.

- The PDF version of the video presentation has these resources starting with slide six:

- National Alliance of Mental Illness’ Suicide Prevention for College Students

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center’s Colleges and Universities webpages detail out importance of prevention and actions schools can take.

- AFSP’s It’s Real: College Students and Mental Health-Documentary on 6 American college students struggling with mental health issues.

- AFSP’s Bring suicide prevention to your school – list of AFSP programs.

- JED's Framework for Developing Institutional Protocols for the Acutely Distressed or Suicidal College Student

“Three Minutes to Save a Life” is an approach which is underpinned by the Connecting with People training delivered by 4 Mental Health. This training program combines the 4 Mental Health modules “Suicide Awareness”, “Self-Harm Awareness,” and “Emotional resilience.” increase compassion, understanding, knowledge and skills for staff, students, and faculty, AND ALSO how to deal with one’s own potential distress by building wellbeing, connectedness, emotional resilience and safety planning. Suicidal thoughts can beset anyone at any time in their life. This program encourages everyone to make a Safety Plan, like the mental health equivalent of putting on a car seat belt. A Safety Plan can equip people with ways to stay safer should they ever experience suicidal thoughts themselves.

Resources:

- University of Wolverhampton’s (United Kingdom) Senior Lecturer in Mental Health and doctoral candidate Clare Dickens discusses “Three Minutes to Save a Life” implemented in her school of nursing (includes article reference, Dickens & Guy 2019, and contact information) available to view here.

- The foundational philosophical overview of Connecting with People training by Dr. Alys Cole-King, Clinical Director 4 Mental Health can be found here.

*This resource originates outside of the United States. Some resources or information may not be applicable or available in the United States.

Nurses and Nursing Students! What Can You Do for Yourself Now?

Self-care is key. Talking about the issue with trusted colleagues and/or a trusted family member or friend is a great start to dealing with the stress caused by this issue. Developing a plan of self-care and encouraging the same for others can mitigate stress and provide a way to deal with oppressive feelings that can beset anyone at any time. Completing a simple, accessible safety plan like Staying Safe at Home’s quick online plan that can help start the process

Thinking about suicide can happen to anyone unexpectantly. Develop a personal safety plan in advance. Be familiar with your resources to make it more likely that you will use available resources when a crisis occurs in your life. This template is self explanatory and helps you to think about warning signs, coping strategies, people who help to calm you or distract you from problems, people to call for help and emergency phone numbers. Once you create your own safety plan, like the one of the two below, you will be better prepared to help a colleague who is in crisis.

Resources:

- Staying Safe at Home’s Safety Plan Templates.

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline offers this link on Safety Plans.

- Well-being Initiative-Nurse-specific mental health and well-being resources.

Mental Health Promotion and Suicide Prevention

Table of Contents:

- Moving from Crisis Intervention to Prevention

- Nurse Mental Health

- Depression and Anxiety

- Help for Nurses

- Burnout

- Compassion Fatigue

- Workplace Violence, Incivility, & Bullying

- Substance Use and Nurse Wellbeing

- Physical Fatigue

- References

DISCLAIMER: The content provided on this webpage is general in nature and does not constitute legal or medical advice. This webpage is for reference only. Always consult with a qualified health care provider for any questions you may have regarding thoughts of suicide. If you believe someone is at imminent risk of harming themselves and is refusing help or you have reason to believe someone has harmed themselves, call 911. Laws vary by jurisdiction, locality, state, or country; please follow the laws of your specific jurisdiction and consult with an attorney if you have any questions regarding the laws of your jurisdiction.

ADDITIONAL DISCLAIMER: Programs, resources, or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage are for illustrative purposes only. ANA does not endorse any program, resource or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage.

These webpages were developed by the Strength through Resiliency Committee, via ANA Enterprise’s Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation initiative.

Moving from Crisis Intervention to Prevention: A Call to Action

Nurses and other clinicians experience high rates of burnout and unhealthy behaviors that can adversely impact the quality and safety of healthcare.1 When compared to the general population, nurses have an increased prevalence of depression, anxiety,2and suicide.3

As a result, the American Nurses Association (ANA) created a national initiative entitled Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation™ in 2017 in order to promote the health and well-being of the largest healthcare workforce in the country.4 In another 2017 initiative, the National Academy of Medicine launched the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-being and Resilience5 in order to bring national visibility to this problem as a public health epidemic and formulate evidence-based solutions to address it.6 A paradigm shift from crisis intervention to mental health promotion and prevention of mental health crises and suicide is urgently needed in the nursing and health professions.

In a national study of over 1,790 nurses from 19 healthcare systems throughout the country, more than half of the nurses reported poor mental and physical health and those in poorer health made more medical errors.7 Depression was the leading cause of medical errors.7 In addition, the longer the shift work, the poorer the nurses’ health. However, those nurses who perceived that their organization supported their well-being had better mental and physical health. These poor health and well-being outcomes in nurses and other clinicians are often the result of healthcare system issues that need remediation, such as inadequate nurse-patient staffing , 12 hour shifts, and extended time having to be spent on tasks and the electronic medical record that take time away from the joy of caring for patients. Nurses do a great job caring for others, but often do not prioritize their own self-care. Urgent action is needed; the current paradigm must shift from one of crisis intervention to health promotion and prevention. Organizations must be more agile to fix system problems, build and sustain wellness cultures, and invest in evidence-based programs and strategies to promote the mental health and well-being of their nursing workforce in order to improve their population health outcomes, reduce costly turnover and ensure the quality and safety of healthcare.

Interventions targeted to individual nurses are more effective when they are integrated with organizational wellness cultures and support.8The Health Policy Institute of Ohio in partnership with The Ohio State College of Nursing Helene Fuld Trust National Institute for Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Health Care released an evidence-based policy brief stating that a multi-stakeholder approach is required to improve nurse wellbeing.9 For sustainable improvements in nurse well-being to occur, state policymakers, health professional licensing boards, healthcare leaders, and health professional colleges and schools must all take action.

Recommended Evidence-based Interventions to Promote Mental Health, Well-being and Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors10

- Mindfulness: ELNEC has compiled a list and descriptions of helpful apps here.

- Cognitive-behavior therapy/skills building

The Ohio State University College of Nursing’s MINDBODYSTRONG Intervention

- Regular deep breathing using the 4, 7, 8 method

- Daily gratitude practices

- Resilience building, see Resilience Resource Center-Everyday Health

- Stress Management and Resiliency Training (SMART)

- Health and wellness coaches: The National Board for Health & Wellness Coaching Directory of Board-Certified Coaches

- Care Giver Support Team

- Prayer

- Meditation

- Yoga

Resources:

- Burnout, Depression and Suicide in Nurses/Clinicians and Learners: An Urgent Call for Action to Enhance Professional Well-being and Healthcare Safety

- Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being

- Making an Evidence-Based Case for Urgent Action to Address Clinician Burnout

- A Call to Action: Improving Clinician Wellbeing and Patient Care and Safety

- Well-Being Initiative – from the American Nurses Foundation

- Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation - (HNHN)-ANA’s nurse wellness program; free and open to all!

- Mental Health Help for Nurses - HNHN blog with practical resources to use NOW!

- Prayer: Compassion in Action: A Guide for Faith Communities Serving People Experiencing Mental Illness and Their Caregivers

Nurse Mental Health

Nurses working in specialty areas with seriously ill, terminal, or traumatized patients seem to show more indications of poor mental health (e.g., increased stress, anxiety, depression, depersonalization, and emotional distress).11,12 These specialties also require nurses to communicate and collaborate with family members who are also hurt and suffering. For all nurses such repetitive emotional exposures often culminate into feelings of compassion fatigue and burnout. Protective measures against compassion fatigue and burnout include resiliency and experience in the field. However, younger nurses may not have fully developed such protective measures due to inexperience,13 therefore, they stand to benefit from guidance provided by the organization, managers, older peer support, and mentors.14,15

Physical fatigue from long hours also plays a role in decreased wellbeing and not only places nurses at risk for burnout but may even affect safe care of the patient. Of high importance is the culture of the organization in which a nurse works as this may negatively or positively affect nurses. Because the amount of distress that a nurse experiences can vary by specialty, addressing nurse mental health requires interventions that target the uniqueness of each individual department and specialty. It is important for organizations to ensure that nurse managers are competent in understanding the risk factors associated with poor mental health outcomes and intervening when these risk factors are recognized.

Recommended Interventions:

- Screen for risk factors by specialty

- Ensure nurse manager competency in leadership, awareness of risk factors, moral and wellness support, mentoring, and role modeling

- Hold evidence-based mindfulness trainings

- Be alert to burnout in young and/or novice nurses and other vulnerable groups, particularly to single male nurses12

- Conduct training for managing difficult encounters

- Provide education on compassion fatigue and resiliency

- Promote mental health, stress reduction and physical wellness in the work environment and at home

- Manage workload and fatigue (long shifts, inadequate rest periods)

- Prioritize a healthy work-life balance

Resources:

- Investigate your Employee Assistance Program (EAP) benefits! They are generally free of cost.

- Interventions to Improve Mental Health, Well-Being, Physical Health, and Lifestyle Behaviors in Physicians and Nurses: A Systematic Review

- A Call to Action: Improving Clinician Wellbeing and Patient Care and Safety

- A Simple Mental Health Pain Scale by The Graceful Patient

Depression and Anxiety

There is a mental health crisis in the field of nursing.16 Suicidal thoughts and action are generally superseded by feelings of depression and anxiety; therefore, it is important for leaders to identify and implement evidence-based screening and intervention programs designed to prevent and mitigate depressive and anxiety symptoms. Any nurse who is depressed should be screened for suicidal ideation.

Classic signs of depression include:

- Changes in appetite

- Vague, generalized pain

- Loss of interest in things one used to enjoy

- Irritability

- Uncontrollable mood changes

- Digestive issues

- Persistent sad thoughts

- Changes in sleep patterns

- Tiredness/fatigue

- Hopelessness and helplessness

- Thoughts of suicide or attempts

NOTE: If feelings of depression and anxiety inhibit your ability to function normally, seek professional advice and therapy from a licensed clinician. If thoughts turn to killing yourself, call or text 988, chat 988lifeline.org, call 911, or go directly to the nearest emergency department.

Although common signs of depression include sadness, loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities, sadness, withdrawal, feelings of worthlessness, decrease in appetite, increase or decrease in sleep, depression may also present with anger, irritability and physical symptoms, such as headaches and fatigue.

The recurrence rate of depression is 50-85%,17so it is important for any nurse affected by depression to receive early evidence-based treatment with cognitive-behavioral therapy/skills building combined with an anti-depressant if symptoms are severe or if suicidal.18 Untreated depression often results in substance use as individuals attempt to regulate their symptoms.

Help for Nurses

Offer the opportunity to be screened anonymously for depression and anxiety symptoms. Two valid and reliable instruments that are fast screens and are free and in the public domain are mdcalc.com’s Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 and mdcalc.com’s General Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 Scales. There also are 2-item versions of both of these scales (i.e., the PHQ-2). When administering these scales, it is critical to have an emergency plan available.

The HEAR (Healer Education Assessment and Referral) screening program is a sustainable suicide prevention program.19 Using an anonymous method, the program provides proactive screening focused on identifying, supporting, and referring clinicians for untreated depression or suicide. Furthermore, it provides education about depression and suicide risk factors.

Depression and anxiety are often co-occurring conditions and do not exist in a vacuum; thus, interventions should be aimed at individual, organizational, and policy levels. Interventions that show promising results for anxiety and depression reduction include developing a positive organizational wellness culture; reducing addiction and mental health stigma; cognitive-behavioral therapy/skills building (this is the first-line evidence-based treatment for mild to moderate depressive symptoms); mindfulness-based stress reduction relational support groups; breath work; and gratitude practices.

Evidence-based Interventions and Resources

- Suicide Prevention: A Healer Education and Referral Program for Nurses

- The MINDBODYSTRONG Intervention for New Nurse Residents: 6-Month Effects on Mental Health Outcomes

- Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction for Psychological Distress Among Nurses: A Systematic Review

- Well-Being Initiative – from the American Nurses Foundation

- Mental Health Help for Nurses- HNHN blog with practical resources to use NOW!

- Taking Care of Yourself – National Alliance on Mental Illness

- Healthcare Professional Burnout, Depression, and Suicide Prevention – The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

Pursuant to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), information regarding an individual’s health or medical information is protected health information, including an individual’s mental health condition. See, 42 U.S.C. § 1320d(4). Therefore, protected health information of an individual should not be shared without that individual’s consent. In the case of a suicide, information regarding the individual’s cause of death should not be shared without the consent of the person(s) with authority to provide consent. 45 C.F.R. §§ 164.508, 164.510.

Burnout

Burnout is experienced by nurses as a result of prolonged and chronic job stressors.20 It is characterized by overwhelming emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, job detachment, and a sense of ineffectiveness. Furthermore, it impacts professional commitment, 21 nurse well-being and retention, patient safety, and patient-family satisfaction.22 The most common factors that impact burnout include: practice environment,22-25 job,21,26 staffing,23,26,27 and leadership support.23,27 Interventions to reduce burnout are vital for nurse wellbeing and fall into two categories: 1) person-directed; or 2) organization-directed.

Help for Nurses

Person-directed interventions include mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques (e.g., Qigong, meditation), cognitive-behavioral therapy/skills building, physical activity, artificial bright light, group therapy, or support provided to individuals.28 Mindfulness-based techniques are of particular importance as studies have shown positive outcomes.29-31 For example, 88% of nurse participants in a mindfulness intervention study demonstrated reduction in stress levels, 90% demonstrated increase in self-compassion, and 19% reported greater satisfaction with life.17 While person-directed interventions have been shown to reduce burnout, the benefit is considered short-lived and typically only lasts up to one month, which is why organizational supports and wellness cultures are essential.8

Work-directed interventions and those with a combined (person and organization directed) are more effective in reducing burnout over a longer term.8 According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine24 the frontline care delivery, health care organization, and external environment all influence each other and contribute to burnout and professional well-being. For this reason, The National Academies recommends a system approach that focuses on structure, organization, and culture of health care to reduce clinician burnout. Lower rates of burnout were seen in nurses with better positive work environments, effective managers, strong nurse-physician relationships, and better staffing.23,26

Evidence-based Recommendations

- Brief mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques may be effective in improving nurse well-being; however, since the positive effects are short-lived, the intervention must be offered continuously.

- Organization-directed interventions, which have longer term effects, should include creating a positive practice environment and developing effective managers who can provide support and advocate for adequate resources.

Resources:

- Avoiding burnout as a nurse from Nursing.org

- Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care from the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)

- NAM’s Taking action against clinician burnout: A systems approach to professional well-being

- Healthcare Professional Burnout, Depression, and Suicide Prevention – The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

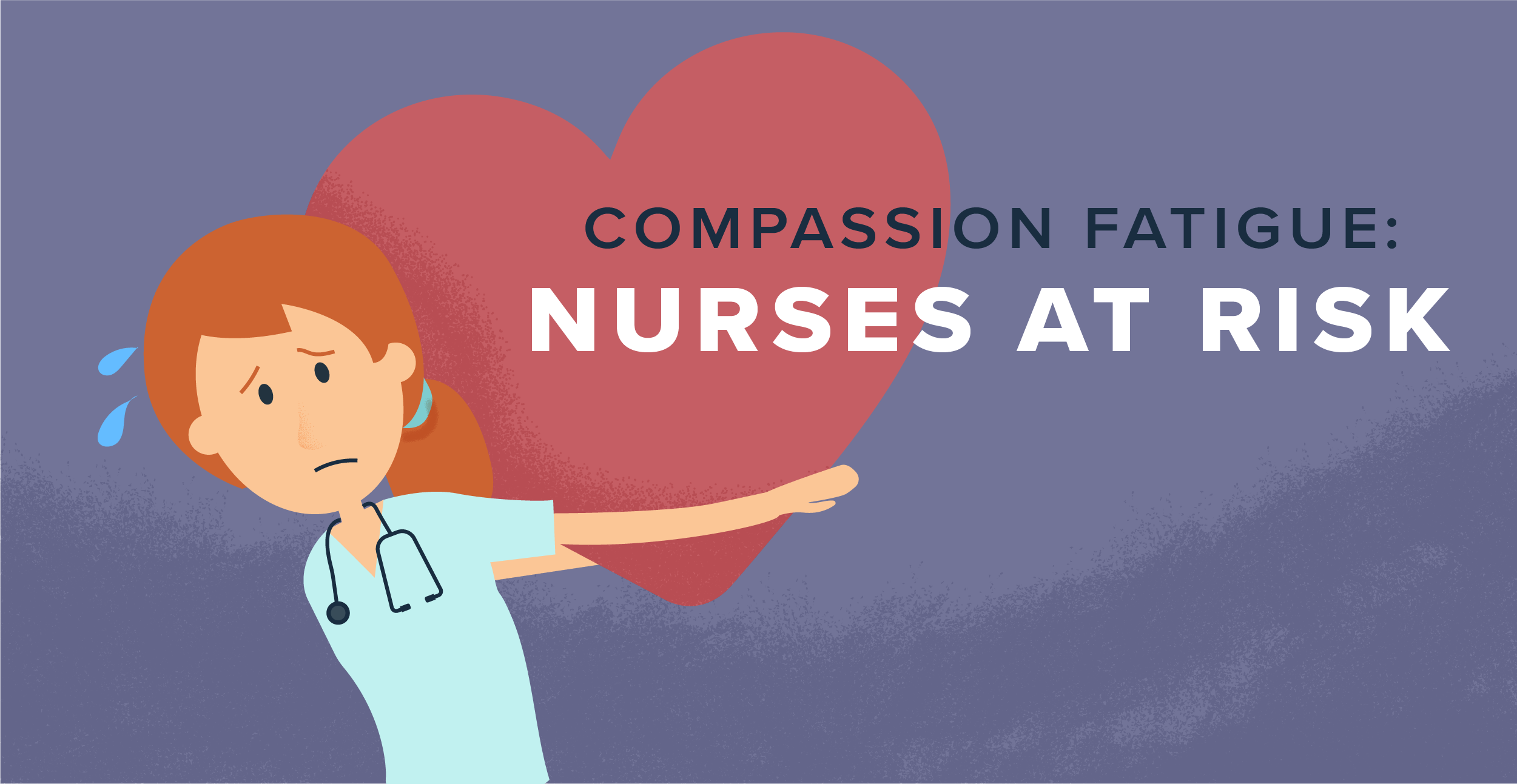

Compassion Fatigue

In a landmark paper, Joinson32 used the term compassion fatigue to describe a set of negative pervasive feelings that are unique to caregivers. These feelings arise from the inability to cope with exposures to patient suffering in addition to institutional barriers to providing quality care and result in losing the ability to nurture. Individuals are attracted to the field of nursing because caring for others is an innate component of their personality, yet, it is this desire to place the needs of others before their own in combination with a uniquely stressful work environment that puts nurses at risk for compassion fatigue. Defining and understanding compassion fatigue can be confusing as the term is often used interchangeably with burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization.33 However, compassion fatigue occurs when a nurse experiences both burnout and secondary traumatic stress simultaneously.34

In nursing, susceptibility to compassion fatigue is most often measured by the ProQoL (i.e., Professional Quality of Life scale).35-45 The ProQoL is a self-assessment tool used to measure compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue (burnout and secondary traumatic stress).35 Once the questions are answered, scores are tallied to measure the level compassion fatigue. The more positive thoughts (i.e., compassion satisfaction) a nurse reports, the less likely they are to experience compassion fatigue.

A number of interventions have been reported to improve compassion satisfaction, but the most successful are those that involve mindfulness, resiliency, and cognitive restructuring. Such interventions have been reported to reduce feelings of compassion fatigue for as long as 6-months.45

Recommendations:

- Measure compassion fatigue via the ProQoL at set intervals as susceptibility can change at any moment depending on the current work stressors. This is self-administered, but can be done by groups for measurement

- Improve compassion satisfaction within the institution by assessing staff needs in addition to evaluating workload, autonomy, choice, and fairness

- Educate and practice interventions including mindfulness, resiliency, and cognitive restructuring

Help for Nurses

- Daily check ins

- Buddy system

- Investigate your Employee Assistance Program (EAP) benefits

Resources:

- Professional Quality of Life Scale – group or self-assessment tool for compassion fatigue

- JustBreathe – deep breathing exercise from OSU

- Stress Management and Resiliency Training (SMART)

- The Compassion Caravan

Workplace Violence, Incivility, & Bullying

Workplace incivility, bullying, and lateral violence (WVIB) in nursing has become a culture within the profession. Patterns of these unreasonable and inappropriate behaviors can result in anger, fear, low self-esteem, disengagement, psychological trauma, depression, suicidal ideation, physical illness, turnover, compassion fatigue, burnout, and personal and organizational financial costs. Complex and pervasive, these forms of actions and behaviors are a “gradually evolving process.”46 From 2010 to the present, mounting research has shown that it is not the individual characteristics such as personality, age, or gender that are correlated as antecedents of WVIB, but rather the organizational culture. For example, all of the following organizational qualities are associated with WVIB: rigid bureaucratic structures; inconsistent bureaucratic structures; lack of procedural justice; misuse of power; rigid and dictatorial leadership styles; role conflict and ambiguity; work stress; disengagement leading to low satisfaction; organizational change; high workloads; high demands; and unclear policies and processes. In addition, WVIB has been correlated with quality of patient care, errors, and patient satisfaction.

The complexity of WVIB, and the uniqueness of organizational cultures has proven, through validated instruments, that focusing only on individual interventions for either the perpetrator and or the target are NOT effective in eliminating WVIB or even effecting a significant sustainable change in behavior. Each organization needs to identify tangible aspects of their culture that are reflected in the behaviors exhibited and believed are expected. This aids in clearly knowing the bullying behaviors actions and /practices that have intentionally or unintentionally been rewarded and encouraged.46 Effective approaches require simultaneously implementation in the areas of: Leadership style, managerial work group behavior, policies and procedures, educational programs, communication processes, and shared locus of control based on a values framework and underlying conceptual theory.

Evidence-based Recommendations:

Assessment of existing culture:

- Valid survey tools focused on organizational issues and not individual behavior need to be utilized for a comprehensive culture assessment of communication processes, power and autonomy and the incidence of WVIB has a correlation with patient safety, staff satisfaction, somatic symptoms, absenteeism, lack of employee engagement, turnover/resignations.

Culture change:

- Implement a zero-tolerance approach and enforce workplace incivility policies

- Needs to be unique to each organization and customized via an assessment of leadership styles, policies, managerial commitment and participation through role modeling behavior of procedural justice, educational training programs.

- Challenge bullying behavior by developing supportive actions to help those being bullied to recover and support bullies to change through team/group focus.

- Have administration commit to anti bullying behavior through a strategic plan based on a values framework, professional code of ethics, teamwork, clear expectations and follow through.

- Address mentorship and preceptor programs to ensure objectivity and reduction of perpetuation of a bullying culture. Aid in socializing new nurses and new employees to a supportive safe culture.

Individual and Team Building Training Programs In:

- Recognizing and responding to WVIB with cognitive rehearsal

- De-escalation techniques in managing incidents, assertive communication at time of event, increasing awareness and insight in other’s perspective so that neither perpetrator nor the bullied become the focus of punishment or reward.

- Anger management

- Negotiation skills

Leadership Styles:

- Supportive and role modeling behaviors such as transactional, transformational and authentic styles, flexible and open to change inclusive of cooperative decision making with employees and managers.

Policy Development and Implementation:

- Implement an anti-bullying policy that ensures zero tolerance and prompt action, provides the appropriate contact(s) for complaints, and prohibits retaliation of any kind for reporting WVIB. Develop policies that focus on preventing WVIB based on best practice evidence. Clarify expectations of behavioral actions with follow through, procedures that promote respect and dignity of all involved- perpetrator, target and bystanders is expected.

- Replacement of Nursing Practice Committees /Councils with a Best Practice Council that is action oriented, utilizes evidence-based data, provided with clear direction and authority, an aggressive timeline and specific intervention and evaluation follow up

Research recommendations:

- Studies are needed to identify consensus definitions of bullying and specific characteristics to the nursing profession. Research is needed to develop an assessment tool that does not address individual behaviors but specific organizational issues, such as structure and communication processes, as a foundation for determining customized interventions.

Resources

- ANA #EndNurseAbuse webpages

- ANA Workplace Violence, Bullying, and Incivility Position Statement-complete with actions nurses and their employers can use for WPVIB prevention and mitigation

- Emergency Nurses Association Workplace Violence webpages

Substance Use and Nurse Wellbeing

Alcohol and drug use among nurses have the potential to harm individual nurses, the nursing workforce, and the provision of care to patients. Unfortunately, the prevalence of risky substance use in nurses and nursing students, or its association with anxiety and depression, is not well described in the literature. Nurses have been reported to have similar substance use disorder rates as the general population,47 although further characterization of the problem is complicated by legal and employment risks to nurses, which likely reduce self-reporting.48,49 Even at levels reported by the general public, this finding indicates that somewhere between one in five and one in seven working nurses actively uses substances in a risky way.50

In nursing, much of the post-licensure literature focuses on substance use disorders or addiction within the nursing profession rather than tracking binge drinking (3+ drinks** in 2 hours for women and 4+ drinks* in 2 hours for men) or drug use that places a person at risk of harm or developing addiction. Other studies have questioned whether a correlation exists between risky substance use and suicidal ideation and suicide completion,3 making substance use a potential target to intervene in the so-called “diseases of despair.” As the surgeon general’s report of 2019 stated, substance use can best be understood using a continuum model of behaviors, ranging from no- or low-risk consumption to moderate/risky consumption above the recommended levels, and finally to high-risk behaviors that include dependency and abuse.51 Halting the progression of risky substance use before actual addiction sets in may be an effective strategy to avoid addiction for at least some people.51

Evidence-based Recommendations and Resources: See this link for additional resources.

Employers:

- Provide universal education regarding substance use for all staff. Consider adding an annual training module regarding substance use risks and healthy limits. Resources from the NCSBN website may be helpful.

- Provide confidential or anonymous opportunities for self-assessment of risky substance use. Consider implementing a program such as the Healer Education, Assessment and Referral (HEAR) Program (Norcross et al., 2018).

- Decrease stigma associated with substance use by encouraging open discussion, easing access to mental health and addiction treatment, and providing opportunities for self-referral (Schmidt & Aly, 2020).

- Consider health practitioner monitoring programs and alternative to discipline programs.

- Provide information to local support groups, including for families of the affected.

Nurses:

- Investigate your Employee Assistance Program (EAP) benefits.

- NCSBN’s Alternative to Discipline Programs for Substance Use Disorder locater by state.

- ANA has a robust Opioid Epidemic webpage. Scroll down to “Substance Use Disorder in Nursing” for multiple resources.

- The American Association of Nurse Anesthetists’ Substance Use Disorder Workplace Resources.

Requirements for reporting individuals who are working while impaired vary by state and organization. For questions regarding your reporting obligations, please consult the rules and regulations for your jurisdiction and organization.

Physical Fatigue

Adults should get 7-9 hours sleep in a 24-hour period and nurses are no exception. With lengthy shifts, prolonged standing, and patient handling and mobility, restorative sleep is a must for all nurses.

In 2011, the Joint Commission published a Sentinel Event Alert warning that (physical) fatigue caused an increase risk to personal safety and well-being of staff. Since then, numerous studies have been published on the adverse effects of fatigue on physicians. Consequently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education began enforcing work hour restrictions in resident programs. Unfortunately, the same focus and outcome has not occurred in nursing. It has been 15 years since a literature review was published on the topic of suicide among nurses,52 and although there have been statistically significant findings regarding physicians and suicide, there has been insufficient data to preclude a meta-analysis on other health-care workers.53 Therefore, more research must be conducted on this subject.

Additionally, research on the topic of physical fatigue and risk of nurse suicide is especially deficient. This could be due to the common opinion that physical fatigue is “part of the job” of nursing.54 If this is indeed the truth, exploration of ways to mitigate physical fatigue should be undertaken as physical fatigue can affect one’s mental wellbeing55 Furthermore, research has found that nurses are particularly vulnerable to the risk of suicide, because they frequently only have one stressor before a suicide attempt, as compared to physicians.56 Given that physical fatigue is part of the nature of a nurse’s work, and that physical fatigue can be seen as a stressor, more efforts should be made towards improving nurse physical fatigue to thwart the incidence of nurse exhaustion.

ANA Fatigue Recommendations:

- Sleep 7-9 consecutive hours within a 24-hour period

- Adjust the sleep environment so it is conductive to sleep (i.e., very dark, comfortable, quiet, and cool in temperature)

- Remove distractions, bright lights, and electronics from your sleep environment (i.e., cell phones, computers, tablets, television)

- Rest before a shift to avoid coming to work fatigued

- Be aware of side effects of over the counter and prescription medications as they may impair alertness and performance

- Improve overall personal health and wellness through stress management, nutrition, and frequent exercise

- Use related benefits and services offered by employers, such as wellness programs, education, and training sessions worksite fitness centers, and designated rest areas

- Take scheduled meals and breaks during the work shift

- Use naps (in accordance with workplace policies)

- Follow established policies, and use existing reporting systems to provide information about accidents

- Follow steps to ensure safety while driving

- Stop driving when drowsy; instead, use a public transportation or call a taxi, friend, or family member for a ride (if necessary, sleep at an alternate site close to work).

- Use naps, caffeine, or both as appropriate in order to be alert enough to drive

- Avoid driving after even small amounts of alcohol when sleep deprived

- Consider the length of a commute prior to applying for employment

- Prior to accepting a position, consider the employer’s demonstrated commitment to establishing a culture of safety and reduction of occupational hazards, including nurse fatigue

Evidence-based Recommendations:

- All areas of nursing (e.g., academia, acute care, and nursing organizations) must work together to mitigate suicide in nursing

- More research needs to be conducted in all aspects for nursing students, practicing nurses (in all areas of nursing), and nurses who have left the profession; especially regarding the association between physical fatigue and risk of suicide

- More assessment for signs and symptoms of suicide should be conducted. Should be part of regular annual health clearance

- Explore the possibility of regulations regarding length of shift per 24-hour period and number of hours per week to decrease physical fatigue

- Explore feasibility of maintaining a journal/record book, documenting physical fatigue scale as well as length of sleep between shifts, such as those used in other industries

Resources:

- Practicing good sleep hygiene

- Talk to your primary care provider about a sleep study

- ANA Fatigue position statement

- NIOSH’s Training for Nurses on Shift Work and Long Work Hours

- Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation

References

- Tawfik, D. S., Scheid, A., Profit, J., Shanafelt, T., Trockel, M., Adair, K. C., Sexton, J. B., & Ioannidis, J. (2019). Evidence Relating Health Care Provider Burnout and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine, 171(8), 555–567. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-1152

- Papathanassoglou, E. D., Karanikola, M., Tsiaousis, G. Z., Giannakopoulou, M., Kaite, C. P., & Mpouzika, M. (2015). Dysfunctional psychological responses among Intensive Care Unit nurses: a systematic review of the literature

- Davidson, J.E., Proudfoot, J., Lee, K., Terterian, G. and Zisook, S. (2020), A Longitudinal Analysis of Nurse Suicide in the United States (2005–2016) With Recommendations for Action. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 17: 6-15. doi:1111/wvn.12419

- American Nurses Association. (2017). Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/hnhn/#:~:text=On%20May%201%2C%202017%2C%20the,nation's%204%20million%20registered%20nurses.

- National Academy of Medicine. (2019). Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. Retrieved from: https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/

- Dzau, V. J., Kirch, D., & Nasca, T. (2020). Preventing a Parallel Pandemic - A National Strategy to Protect Clinicians' Well-Being. The New England journal of medicine, 10.1056/NEJMp2011027. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2011027

- Melnyk, B. M., Orsolini, L., Tan, A., Arslanian-Engoren, C., Melkus, G. D., Dunbar-Jacob, J., Rice, V. H., Millan, A., Dunbar, S. B., Braun, L. T., Wilbur, J., Chyun, D. A., Gawlik, K., & Lewis, L. M. (2018). A National Study Links Nurses' Physical and Mental Health to Medical Errors and Perceived Worksite Wellness. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 60(2), 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001198

- Westermann, C., Kozak, A., Harling, M., & Nienhaus, A. (2014). Burnout intervention studies for inpatient elderly care nursing staff: Systematic literature review. International journal of nursing studies, 51(1), 63-71.

- The Health Policy Institute of Ohio in partnership, & The Ohio State College of Nursing Helene Fuld Trust National Institute for Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Health Care. (2020). A call to action: Improving clinician wellbeing and patient care and safety. Available at: https://www.healthpolicyohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CallToAction_Brief.pdf

- Melnyk, B. M., Kelly, S. A., Stephens, J., Dhakal, K., McGovern, C., Tucker, S., Hoying, J., McRae, K., Ault, S., Spurlock, E., & Bird, S. B. (2020). Interventions to Improve Mental Health, Well-Being, Physical Health, and Lifestyle Behaviors in Physicians and Nurses: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Health Promotion : AJHP, 890117120920451. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120920451

- Cañadas‐De la Fuente, G.A., Gómez‐Urquiza, J.L., Ortega‐Campos, E.M., Cañadas, G.R., Albendin-Garcia, L., De la Fuente-Solana, E.I. (2018). Prevalence of burnout syndrome in oncology nursing: A meta analytic study. Psycho‐Oncology, 27, 1426-1433.

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L., De la Fuente-Solana, E.I., Albendín-García, L., Vargas-Pecino, C., Ortega-Campos, E.M., Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. (2017) Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in Emergency Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Critical Care Nurse, 37.

- Park E, Meyer RML, Gold JI. The role of medical specialization on posttraumatic symptoms in pediatric nurses. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 53 (2020) 22-28.

- Lavoie, S., Talbot, L. R., & Mathieu, L. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among emergency nurses: Their perspective and a “tailor-made” solution. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(7), 1514–1522.

- Lopez-Lopez IM, Gomez-Urquiza JL, Cañadas GR, De la Fuente EI, Albendın-Garcıa L, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Prevalence of burnout in mental health nurses and related factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing (2019) 28, 1032–1041.

- Melnyk, B.M. (2020), Burnout, Depression and Suicide in Nurses/Clinicians and Learners: An Urgent Call for Action to Enhance Professional Well‐being and Healthcare Safety. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 17: 2-5. doi:10.1111/wvn.12416

- Sim, K., Lau, W. K., Sim, J., Sum, M. Y., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2015). Prevention of Relapse and Recurrence in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Controlled Trials. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 19(2), pyv076. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyv076

- Cuijpers P, Noma H, Karyotaki E, Vinkers CH, Cipriani A, Furukawa TA. A network meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and their combination in the treatment of adult depression. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):92-107. doi:10.1002/wps.20701

- Davidson, J. E., Accardi, R., Sanchez, C., Zisook, S., & Hoffman, L. A. (2020). Sustainability and Outcomes of a Suicide Prevention Program for Nurses. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing, 17(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12418

- Maslach, C. (1998). A multidimensional theory of burnout. Theories of organizational stress, 68, 85.

- Jourdain, G., & Chênevert, D. (2010). Job demands–resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: A questionnaire survey. International journal of nursing studies, 47(6), 709-722.

- Buckley, L., Berta, W., Cleverley, K., Medeiros, C., & Widger, K. (2020). What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: a scoping review. Human resources for health, 18(1), 9.

- Hanrahan, N. P., Aiken, L. H., McClaine, L., & Hanlon, A. L. (2010). Relationship between psychiatric nurse work environments and nurse burnout in acute care general hospitals. Issues in mental health nursing, 31(3), 198-207.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25521.

- Vander Elst, T., Cavents, C., Daneels, K., Johannik, K., Baillien, E., Van den Broeck, A., & Godderis, L. (2016). Job demands–resources predicting burnout and work engagement among Belgian home health care nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nursing outlook, 64(6), 542-556.

- Leineweber, C., Westerlund, H., Chungkham, H. S., Lindqvist, R., Runesdotter, S., & Tishelman, C. (2014). Nurses' practice environment and work-family conflict in relation to burn out: a multilevel modelling approach. PLoS One, 9(5).

- Toh, S. G., Ang, E., & Devi, M. K. (2012). Systematic review on the relationship between the nursing shortage and job satisfaction, stress and burnout levels among nurses in oncology/haematology settings. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 10(2), 126-141.

- Ahola, K., Toppinen-Tanner, S., & Seppänen, J. (2017). Interventions to alleviate burnout symptoms and to support return to work among employees with burnout: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Burnout Research, 4, 1-11.

- Gilmartin, H., Goyal, A., Hamati, M. C., Mann, J., Saint, S., & Chopra, V. (2017). Brief mindfulness practices for healthcare providers–a systematic literature review. The American journal of medicine, 130(10), 1219-e1.

- Nowrouzi, B., Lightfoot, N., Larivière, M., Carter, L., Rukholm, E., Schinke, R., & Belanger-Gardner, D. (2015). Occupational stress management and burnout interventions in nursing and their implications for healthy work environments: A literature review. Workplace health & safety, 63(7), 308-315.

- Shapiro, S. L., Astin, J. A., Bishop, S. R., & Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. International journal of stress management, 12(2), 164.

- Joinson C. (1992). Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing, 22(4), 116–120.

- Coetzee SK, Klopper HC. Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: a concept analysis. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12(2):235-243. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00526.x

- Professional Quality of Life Measure. (2019a). Compassion Fatigue. Retrieved from https://proqol.org/Compassion_Fatigue.html

- Professional Quality of Life Measure. (2019b). The ProQol Measure in English and Non-English. Retrieved from: https://proqol.org/ProQol_Test.html

- Slatyer, S., Craigie, M., Heritage, B., Davis, S., & Rees, C. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of a brief mindful self-care and resiliency (MSCR) intervention for nurses: A controlled trial. Mindfulness, 9(2), 534-546.

- Duarte, J., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2016). Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on oncology nurses’ burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms: A non-randomized study. International journal of nursing studies, 64, 98-107.

- Craigie, M., Slatyer, S., Hegney, D., Osseiran-Moisson, R., Gentry, E., Davis, S., ... & Rees, C. (2016). A pilot evaluation of a mindful self-care and resiliency (MSCR) intervention for nurses. Mindfulness, 7(3), 764-774.

- Yılmaz, G., Üstün, B., & Günüşen, N. P. (2018). Effect of a nurse‐led intervention programme on professional quality of life and post‐traumatic growth in oncology nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 24(6), e12687.

- Jakel, P., Kenney, J., Ludan, N., Miller, P. S., McNair, N., & Matesic, E. (2016). Effects of the use of the provider resilience mobile application in reducing compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical journal of oncology nursing, 20(6), 611-616.

- Hevezi, J. A. (2016). Evaluation of a meditation intervention to reduce the effects of stressors associated with compassion fatigue among nurses. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 34(4), 343-350.

- Flanders, S., Hampton, D., Missi, P., Ipsan, C., & Gruebbel, C. (2020). Effectiveness of a Staff Resilience Program in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Journal of pediatric nursing, 50, 1-4.

- Flarity, K., Nash, K., Jones, W., & Steinbruner, D. (2016). Intervening to improve compassion fatigue resiliency in forensic nurses. Advanced emergency nursing journal, 38(2), 147-156.

- Wahl, C., Hultquist, T. B., Struwe, L., & Moore, J. (2018). Implementing a peer support network to promote compassion without fatigue. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(12), 615-621.

- Klein, C. J., Riggenbach-Hays, J. J., Sollenberger, L. M., Harney, D. M., & McGarvey, J. S. (2018). Quality of life and compassion satisfaction in clinicians: a pilot intervention study for reducing compassion fatigue. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 35(6), 882-888.

- Pheko, M. M., Monteiro, N. M., & Segopolo, M. T. (2017). When work hurts: A conceptual framework explaining how organizational culture may perpetuate workplace bullying. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(6), 571-588.

- Worley, J. (2017). Nurses with substance use disorders. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 55(12): 11-14.

- Foli, K., Reddick, B., Zhang, L. & Krcelich, K. (2020). Substance use in registered nurses: “I Heard About a Nurse Who . . .” Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 26(1): 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390319886369.

- Monroe, T., Kenaga, H., Dietrich, M., Carter, M., & Cowan, R. (2013). The prevalence of employed nurses identified or enrolled in substance use monitoring programs. Nursing Research, 62(1): 10–15. https//doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e31826ba3ca.

- Starr, K. (2015). The sneaky prevalence of substance abuse in nursing. Nursing2015 March: 16-17: https//doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000460727.34118.6a.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: HHS, November 2016.

- Alderson, M. Parent-Rocheleu, X, & Mishara, B. (2015). Critical review on suicide among nurses. Crisis, 36(2), 91-101. DOI: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000305

- Dutheil, F., Aubert, C., Pereira, B., Dambrun, M., Moustafa, F., Mermillod, M., Baker, J., Trousselard, M., Lesage, F., & Navel, V. (2019). Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 14(12), DOI.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226361

- Rogers, A. (2019). Nurses’ work schedules, quality of care, and the health of the nurse workforce remain significant issues. Washington State Nurses Association.

- Zeng, H.J., Zhou, G.Y., Yan, H.H., Yang, X.H. & Jin, H.M. (2018). Chinese nurses are at high risk for suicide: A review of nurses suicide in China 2007-2016. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32, 896-900. Doi.org/10/1016/j.apnu.2018.07.005

- Braquehais, M., Eiroa-Orosa, F., Holmes, K., Lusilla, P., Bravo, M., Mozo, X., Mezzatesta, M., Casanovas, M., Pujol, T., & Sher, L. (2016). Differences in physicians’ and nurses’ recent suicide attempts: An exploratory study. Archives of Suicide Research, 20(2), 273-279. DOI:10.1080/13811118.2014.996693

Grief, Bereavement, & Healing in the Aftermath of Co-worker Suicide

Table of Contents:

- Grieving

- Honoring the Memory

- Preventing Future Suicides and Providing Mental Health at the Workplace

DISCLAIMER: The content provided on this webpage is general in nature and does not constitute legal or medical advice. This webpage is for reference only. Always consult with a qualified health care provider for any questions you may have regarding thoughts of suicide. If you believe someone is at imminent risk of harming themselves and is refusing help or you have reason to believe someone has harmed themselves, call 911. Laws vary by jurisdiction, locality, state, or country; please follow the laws of your specific jurisdiction and consult with an attorney if you have any questions regarding the laws of your jurisdiction.

ADDITIONAL DISCLAIMER: Programs, resources, or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage are for illustrative purposes only. ANA does not endorse any program, resource or information mentioned or referred to on any webpage.

When a nurse dies by suicide, it profoundly impacts their co-workers and the work environment. Grief, guilt, sadness, unease, fear, anger, and other emotions flood those left behind. In order to navigate this difficult time, employees, employers, and supervisors must come together in order to grieve, honor the deceased’s memory, prevent further death and mental anguish, heal, and come through stronger following the recovery process.

Words matter - to reduce the stigma the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) recommends use of completed or attempted suicide terminology over committed suicide as it is not a crime but the result of a mental health crisis.

Grieving

Nurses are well-acquainted with the death of patients, but not the passing of co-workers. At work, we often see our co-workers more frequently and for longer time periods than our immediate family members. The nature of the job lends itself to developing close ties with other nurses. Special bonds are forged over the good, like delivering a healthy baby, and the bad, like an unsuccessful code; unique experiences that others may never fully comprehend. Losing a co-worker can be devastating; in situations where the death is by suicide, the grieving often becomes more complex. Grief to a loss by suicide may include survivors questioning, “why didn’t I know?” and mistakenly believing that suicide is a choice rather than a manifestation of a symptom of a mental condition.

Grief can follow loss and may also occur following an attempted suicide by a co-worker. This is a disruption of the previous homeostasis in your workplace.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross outlined five predictable stages of grief in her book On Death and Dying, published in 1969. Below is a reminder of these stages, which were updated more recently by David Kressler, adding the two additional processing stages of shock and testing (*).

- Shock*

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Testing*

- Acceptance

It’s important to remind ourselves that this list isn’t meant to be used as a checklist to complete in order to demonstrate we have achieved competence in grieving. Grief is a process and one that is unique to each individual who experiences a loss. The feelings you experience are yours. There isn’t a right and a wrong way to do it. There are, however, healthy and unhealthy ways to work through our grief. We must take the time to adequately grieve. Below find specially curated resources to assist with grief management for yourself and to share with colleagues. Reactions to grief can be both physical and psychological, be sure to address overall well-being as you navigate healing. Processing grief is different for each person and has no specific timeline.

Important: If you’re having overwhelming feelings of grief or depression, seek professional advice and therapy from a licensed clinician. If you have thoughts of suicide or harming yourself, call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org. These connect to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Resources

-