Healthcare Associated Infections

Background

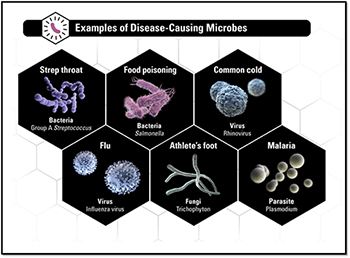

Health care-associated infections (HAIs), are acquired while patients are receiving treatment for another condition in a health care setting. HAIs can occur anywhere health care is delivered, including inpatient acute care hospitals, outpatient settings such as ambulatory surgical centers or dialysis facilities, and long-term care facilities such as nursing homes and rehabilitation centers. HAIs may be caused by any infectious agent, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, as well as other less common types of pathogens.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has identified the reduction of HAIs as an Agency Priority Goal and is committed to reducing the national rate of HAIs by demonstrating significant, quantitative, and measurable reductions in hospital-acquired central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), as a start.

For more information:

- National Action Plan to Prevent Health Care-Associated Infections: Road Map to Elimination

https://health.gov/our-work/health-care-quality/health-care-associated-infections - CDC-HAI Data and Statistics

http://www.cdc.gov/hai/surveillance/

Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infection (CLABSI)

Types of vascular-access catheters

Types of vascular-access catheters

Choice of catheter should be based on the intended purpose of the line and projected duration of use.

- Nontunneled central venous catheters (CVCs). These lines are inserted percutaneously, with the tip resting in a central vein. They’re used for longer-term I.V. therapy with vesicants and irritants, large-volume resuscitation, and invasive monitoring. These catheters are the type most commonly associated with central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends avoiding use of the femoral vein in adults because of the higher infection rate. It also recommends using the subclavian site unless the patient has advanced renal disease and needs to avoid the risk of stenosis at a future dialysis catheter site.

- Pulmonary artery catheters. These lines are inserted through an introducer catheter in a central vein, with the tip floating in the pulmonary artery. Used to monitor pressures within the heart, they have similar CLABSI rates as other nontunneled CVCs; however, the subclavian site has a lower risk. During insertion, use a sterile sleeve on this catheter to reduce infection risk.

- Peripherally inserted CVCs. Used when therapy is expected to last more than 6 days, these catheters are inserted through the basilic, cephalic, or brachial vein, with the tip in the superior vena cava. They have lower CLABSI rates than nontunneled CVCs.

- Tunneled CVCs. Implanted into the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral vein, tunneled CVCs have a cuff below the skin that helps prevent migration of organisms down the catheter track. This gives them a lower CLABSI rate than nontunneled CVCs.

- Totally implantable catheters. Implanted in the subclavian or internal jugular vein, these lines have a subcutaneous port that’s accessed with a needle. Totally implantable catheters have the lowest CLABSI risk of all central lines.

- Umbilical catheters. These lines are inserted into the umbilical artery or vein; CLABSI risk is similar in both vessels. CDC recommends dwell times not exceed 5 days for an arterial catheter or 14 days for a venous umbilical catheter.

Non-central line catheters, such as peripheral venous, peripheral arterial, and midline catheters, rarely are associated with CLABSI.

From ANT, September 2015 Vol. 10 No. 9

By the Numbers

- About 41,000 bloodstream infections strike hospital patients with central lines each year

- About 37,000 bloodstream infections happen each year to kidney dialysis patients with central lines

- Of patients who get a bloodstream infection from having a central line, up to 1 in 4 die

- However, by using evidence based infection prevention & control steps:

- Between 2008 and 2014, CLABSIs in acute care hospitals decreased by 50%

- In long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), between 2013-2014, reported CLABSIs decreased by 9%

Bundles, Guidelines & Toolkits

- AHRQ-CLABSI Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP)

http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/clabsitools/index.html#purpose- Designed to support unit efforts to implement evidence-based practices and eliminate CLABSIs

- Aligns with the E's found in the CUSP toolkit:

- Engage: How will this make the world a better place?

- Educate: How will we accomplish this?

- Execute: What do I need to do?

- Evaluate: How will we know we made a difference?

- APIC Implementation Guide to preventing CLABSI

https://apic.org/resources/topic-specific-infection-prevention/central-line-associated-bloodstream-infections/

- Outlines practices that are core to central line-associated bloodstream infection prevention efforts

- Chapter Topics include:

- Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

- Surveillance

- Adherence to the Central Line Bundle

- Preventing Infections during Catheter Maintenance

- Preventing Infection during Long-Term Device Use

- CDC CLABSI in Non-ICU settings toolkit

http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/toolkits/CLABSItoolkit_white020910_final.pdf- Comprehensive PowerPoint

- Includes statistics, common areas of concern, and practice guidelines

- CDC Guidelines for Prevention of CLABSI

http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/guidelines/bsi-guidelines-2011.pdf- Detailed, evidence based guideline

- Summary of recommendations, pages 9-21

- CMMS—Resources—CLABSI

https://partnershipforpatients.cms.gov/p4p_resources/tsp-centralline-associatedbloodstreaminfections/toolcentralline-associatedbloodstreaminfectionsclabsi.html- Links & descriptions

- Multilingual and pediatric resources

- FAQs-CLABSI: Patient education flyer

http://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/bsi/BSI_tagged.pdf

- IHI How to Guide-Prevent CLABSI

http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/HowtoGuidePreventCentralLineAssociatedBloodstreamInfection.aspx- Requires free sign-in to access, detailed

- Clearly defines CLABSI bundle to include:

- Hand hygiene

- Maximal barrier precautions

- Chlorhexidine skin antisepsis

- Optimal catheter site selection, with avoidance of using the femoral vein for central venous access in adult patients

- Daily review of line necessity, with prompt removal of unnecessary lines

- Concrete templates for establishing a CLABSI CUSP

- The Joint Commission-Preventing Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections: Useful Tools, An International Perspective – Tools Directory (hyperlinked chapters)

http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/CLABSI_Toolkit_Tools_Directory_linked.pdf

Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI)

By the Numbers

By the Numbers

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the fourth most common type of healthcare-associated infection, with an estimated 93,300 UTIs in acute care hospitals in 2011, accounting for more than 12% of infections reported by acute care hospitals

- Among UTIs acquired in the hospital, approximately 75% are associated with a urinary catheter

- The most important risk factor for developing a catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is prolonged use of the urinary catheter

- However, by using evidence based infection prevention & control steps:

- No increase in overall CAUTIs in acute care hospitals between 2009 and 2014

- 11% decrease in CAUTI in long term care facilities between 2013 and 2014

- 14% decrease in CAUTI in inpatient rehabilitation facilities between 2013 and 2014

Bundles, Guidelines & Toolkits

- AHRQ—CUSP Toolkit

http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/cusptoolkit/toolkit/index.html- The core CUSP Toolkit and each module are built on the following framework:

- Facilitator notes

- Slides

- Videos

- Tools

- Need time to master, but comprehensive and standardized

- The core CUSP Toolkit and each module are built on the following framework:

- ANA CAUTI Prevention Tool

https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/infection-prevention/ana-cauti-prevention-tool/- Partnership with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Partnership for Patients (PfP) in an effort to reduce avoidable HAIs by 40% and reduce 30-day hospital readmissions by 20%

- Toolkit in flow diagram format: brief, succinct

- Links to additional resources

- APIC CAUTI Resource Webpage

https://apic.org/Resources/Topic-specific-infection-prevention/Catheter-associated-urinary-tract-infection/- Links to guidelines, education, and prevention strategies

- Tabs for healthcare professional and general consumer

- CDC—CAUTI Toolkit

http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/toolkits/CAUTItoolkit_3_10.pdf- PowerPoint, comprehensive

- Statistics, visuals, core strategies

- CMMS—Resources—CAUTI

https://partnershipforpatients.cms.gov/p4p_resources/tsp-catheterassociatedurinarytractinfections/toolcatheter-associatedurinarytractinfectionscauti.html- Links & descriptions

- Bundles and toolkits

- FAQs—CAUTI education flyer

- IHI - How-to Guide: Prevent Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/HowtoGuidePreventCatheterAssociatedUrinaryTractInfection.aspx- Requires free sign-in to access

- Four core concepts:

- Avoid unnecessary urinary catheters

- Insert urinary catheters using aseptic technique

- Maintain urinary catheters based on recommended guidelines

- Review urinary catheter necessity daily and remove promptly

- Provides guidance for establishing metrics

- The Joint Commission—CAUTI Resource Page (hyperlinked chapters)

http://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/uti/CA-UTI_tagged.pdf- Articulation of National Patient Safety Goals

- Links to other resources

Antimicrobial Resistance

- At least 2 million people in the US become infected with microbes that are resistant to antibiotics and at least 23,000 people die each year as a direct result of these infections, according to the CDC

- A 2014 study found that up to half of hospitalized patients received at least one antibiotic and in 30% to 50% of these cases, antibiotics were not needed or inappropriate

- One of the key actions to minimize anti-microbial resistance (AMR) is to improve the way antibiotics are used

Information & Guidelines

Information & Guidelines

-

ANA/ANT - Antibiotic stewardship for staff nurses

https://www.myamericannurse.com/antibiotic-stewardship-staff-nurses/

- 5 key steps for nursing interventions

- Great resource list

- APIC Antimicrobial stewardship resource page

https://apic.org/Professional-Practice/Practice-Resources/Antimicrobial-Stewardship/- Consolidated webpage listing

- Guidelines, toolkits & editorials

- CDC - About Antimicrobial Resistance

http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/about.html- AMR primer

- Great graphics and visuals

- NQF/NQP Antibiotic Stewardship Playbook

http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2016/05/Antibiotic_Stewardship_Playbook.aspx?utm_source=internal&utm_medium=link&utm_term=ABX&utm_content=Playbook&utm_campaign=ABX- Comprehensive tome on how to establish an institutional ASP

- Builds on CDC’s core elements

General HAI Information & Resources

|

Media Type |

Year |

Name |

Webpage |

Description |

Comments |

|

💻 Website |

2014 |

AHA Fast Facts on US Hospitals |

http://www.aha. |

Statistics on US hospitals by type and geography |

Can also present as pie charts |

|

💻 Website |

2015 |

American Nurse Today Special Edition: Infection Prevention |

https://www. myamericannurse.com/ special-reports/special-report-infection-prevention/ |

Covers CLABSI, CAUTI, SSI, VAP |

Consolidated compendium, RN focused |

|

💻 Website |

Varied |

APIC Implementation Guides |

https://apic.org/ Professional-Practice/ Implementation-guides/ |

Consolidated webpage of infection prevention guidelines |

Glossary list |

|

💻 Website |

Ongoing |

APIC Infection Prevention & You |

http:// |

Consumer-focused; covers a variety of infection prevention topics |

Infographics, great resources for beginner through expert |

|

💻 Website |

2014 |

CDC Antibiotic Resistance Patient Safety Atlas |

Search data about antibiotic-resistant HAIs reported from 4,000+ U.S. hospitals |

Dynamic mapping across the US by microbe |

|

|

💻 Website |

2015 |

CDC Dialysis Safety |

Hemodialysis patients are at high risk for HAIs because the frequent use of catheters or insertion of needles to access the bloodstream. The website specifically addresses the needs of this vulnerable population. |

Tile driven, well organized for clinician and patient |

|

|

💻 Website |

2015 |

CDC/HICPAC Publications |

Consolidated resource page for relevant infection prevention guidelines |

Requires time to review |

|

|

💻 Website |

Ongoing |

CDC/MMWR National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) |

http://wonder. |

Statistical data of reportable diseases |

Cumbersome database |

|

💻 Website |

2015 |

CDC/NHSN - Tracking Infections in Acute Care Hospitals/ Facilities |

Extensive by HAI resources for reporting |

Lots of training videos |

|

|

💻 Website |

2015 |

CDC State-based HAI Prevention Activities |

State by state quick look of HAI activities. |

Presents snapshot graphics of HAI data. |

|

|

💻 Website |

Top CDC Recommendations to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections |

http://www.cdc. |

2-page flyers with prevention strategies for CAUTI, SSI, CLABSI, C. Difficile, and MRSA |

Provides basic steps and other practices to consider. Easy to evaluate and take away appropriate practices |

|

|

💻 Website |

2011 |

CDC Vital Signs: Making Healthcare Safer – reducing bloodstream infections |

Four pages; good statistics, but 2011 data. Overview of CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network role. |

Historical document |

Last edited 4/26/2016

Ventilator Associated Event/Pneumonia

Nursing practices that help prevent VAP

Several basic nursing practices contribute to successful efforts to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

Practice proper hand hygiene.

The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) remind practitioners that adhering to hand hygiene protocol is essential to prevent transmission of bacteria when caring for mechanically ventilated patients. CDC recommends wearing gloves when handling respiratory secretions and for contact with objects contaminated by respiratory secretions.

Verify feeding-tube placement and take steps to prevent aspiration.

Routinely verify proper feeding-tube placement. To help prevent aspiration associated with enteral feedings, monitor gastric residual volume and assess for signs and symptoms of gastric overdistention.

Routinely verify endotracheal tube cuff pressure.

Measure endotracheal tube cuff pressure directly; maintain pressure between 20 and 25 cm H2O. Properly inflated cuff pressure helps prevent microaspiration, VAP, and tracheal injury.

From ANT, September 2015 Vol. 10 No. 9

By the Numbers

- Definition:

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a nosocomial lung infection that occurs in patients receiving mechanical ventilation and for whom the infection was not the reason for ventilation

- Pneumonia is considered as ventilator-associated if the patient was intubated and ventilated at the time or within 48 hours before the onset of infection

- VAP risk rises 1% to 3% every day the patient remains on mechanical ventilation

- With surgical site infections, accounts for close to ¼ of all hospital infections

Bundles, Guidelines & Toolkits

- CDC - Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

http://www.cdc.gov/rsv/index.html- The most common cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children in the US younger than 1 year

- Clinician guidelines and resources

- CDC - VAP and non-ventilator-associated Pneumonia [PNEU] Event

http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/6pscVAPcurrent.pdf- Surveillance criteria for bacterial pneumonia in ICU patients who are mechanically ventilated

- Definitions & algorithms, including laboratory findings for adult and pediatric patients

- CMMS—Resources—VAP

https://partnershipforpatients.cms.gov/p4p_resources/tsp-ventilator-associatedpneumonia/toolventilator-associatedpneumoniavap.html- Links & descriptions

- Business plans as well as clinician guides

- FAQs—VAP

http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/vap/VAP_tagged.pdf

- IHI—How-to Guide: Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

http://www.ihi.org/resources/pages/tools/howtoguidepreventvap.aspx- Requires free sign-in to access

- Detailed compendium centered around the 5 key components as listed under AACN

- Includes examples for outcome measurement

VAP: Clinical Focus (Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia)

The Scope of the Problem

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is one of the most common hospital-acquired infections and can impact more than 20% of mechanically ventilated patients. It is associated with:

- Increased morbidity and mortality — Mortality rates vary but may exceed 10%

- Prolonged mechanical ventilation

- Increased hospital length of stay — by 2 days

- Extended use of antimicrobial medication

- Increased costs — $40,000 per patient or $1.2 billion annually in the United States.

VAP occurs as a result of a bacterial infection of the pulmonary parenchyma of mechanically ventilated patients. Infection can occur as a result of some bacterial invasion of the sterile lower respiratory tract such as aspiration, use of contaminated equipment, ingestion of contaminated medications, or colonization of the aerodigestive tract. Consequently, the development of a standard, reliable, and valid definition for VAP has been difficult to identify.

(AACN, 2016) http://www.aacn.org/dm/resource/resourceportal.aspx?menu=practice&topic=vap

|

Element |

Practice |

Evidence |

Rationale |

|

Perform hand hygiene before and after touching the patient or the ventilator |

|||

|

Daily spontaneous awakening trials and spontaneous breathing trials |

|

I. High Highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimated size and direction of the effect. Evidence is rated as high quality when there is a wide range of studies with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval. |

|

|

Maintain head of bed 30-45 degrees as long as tolerated |

|

III. Low The true effect may be substantially different from the estimated size and direction of the effect. Evidence is rated as low quality when supporting studies have major flaws, there is important variation between studies, the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide, or there are no rigorous studies, only expert consensus. |

A meta-analysis found a significant impact on VAP. In addition, enteral feeding in the supine position substantially increases the risk of developing VAP. |

|

Use an endotracheal tube with a dorsal lumen above the cuff to allow drainage by continuous suctioning of tracheal secretions that accumulate in the subglottic area |

Endotracheal tubes with subglottic secretion drainage ports are therefore recommended only as a basic practice for patients likely to require greater than 48–72 hours of intubation. |

II. Moderate The true effect is likely to be close to the estimated size and direction of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Evidence is rated as moderate quality when there are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there is some variation between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide. |

Provide endotracheal tubes with subglottic secretion drainage ports for patients likely to require greater than 48 or 72 hours of intubation |

|

Perform regular oral care minimally every 12 hours |

|

Limited evidence to support practice, although there is increasing evidence being published |

Association between oral microbiome and respiratory pathogens causing pneumonia |

|

Minimize disruption to circuit, inspect ventilator circuit for gross contamination daily and if present change circuit. Remove condensation from the ventilator circuit and keep the circuit closed during removal |

|

I. High Highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimated size and direction of the effect. Evidence is rated as high quality when there is a wide range of studies with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval |

Change the ventilator circuit only if visibly soiled or malfunctioning |

Solutions for Patient Safety, 2016 (http://www.solutionsforpatientsafety.org/wp-content/uploads/SPS-Prevention-Bundles.pdf)

Michael Klompas, Richard Branson, Eric C. Eichenwald, Linda R. Greene, Michael D. Howell, Grace Lee, Shelley S. Magill, Lisa L. Maragakis, Gregory P. Priebe, Kathleen Speck, Deborah S. Yokoe and Sean M. Berenholtz (2014). Strategies to Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 35, pp 915-936. doi:10.1086/677144.

Clostridium Difficile (C. diff)

By the Numbers

- Definition:

- Clostridium difficile is an spore forming bacterium that causes colitis and diarrhea

- Opportunistic infection caused when there is an imbalance in gut flora

- Shed in feces

- Transferred to patients mainly via the hands from those who have touched a contaminated surface or item

- Responsible for 14,000 deaths annually

- Almost all C. difficile infections are connected to getting medical care

- Almost half of infections occur in people younger than 65, but more than 90% of deaths occur in people 65 and older

- Hospitals following infection control recommendations lowered C. difficile infection rates by 20% in less than 2 years

Bundles, Guidelines & Toolkits

- APIC - Guide to Preventing Clostridium difficile Infections

https://apic.org/resources/topic-specific-infection-prevention/clostridium-difficile/

- Comprehensive, good epidemiological data

- Algorithms, sample environmental and facility transfer checklists

- CDC HAIs - Clostridium difficile Infection

http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/cdiff/Cdiff_infect.html- Resources for clinicians and general public

- Links for disease tracking, facility management, and specific state initiatives

- CDC C. diff Guidelines and Prevention Resources

https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/clinicians/resources.html - FAQs—Clostridium difficile

http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/cdiff/Cdiff_tagged.pdf

- GNYHA/UHF C. difficile Collaborative - Reducing c. difficile infections toolkit

https://apic.org/Resource_/TinyMceFileManager/Practice_Guidance/cdiff/C.Diff_Digital_Toolkit_GNYHA.pdf- Online toolkit

- Comprehensive, but easy to navigate

For Clinicians: 6 Steps to Prevention

- Prescribe and use antibiotics carefully. About 50% of all antibiotics given are not needed, unnecessarily raising the risk of C. difficile infections.

- Test for C. difficile when patients have diarrhea while on antibiotics or within several months of taking them.

- Isolate patients with C. difficile immediately.

- Wear gloves and gowns when treating patients with C. difficile, even during short visits. Hand sanitizer does not kill C. difficile, and hand washing may not be sufficient.

- Clean room surfaces with bleach or another EPA-approved, spore-killing disinfectant after a patient with C. difficile has been treated there.

- When a patient transfers, notify the new facility if the patient has a C. difficile infection

(CDC, 2012)